Case Study: Assignment Library Search

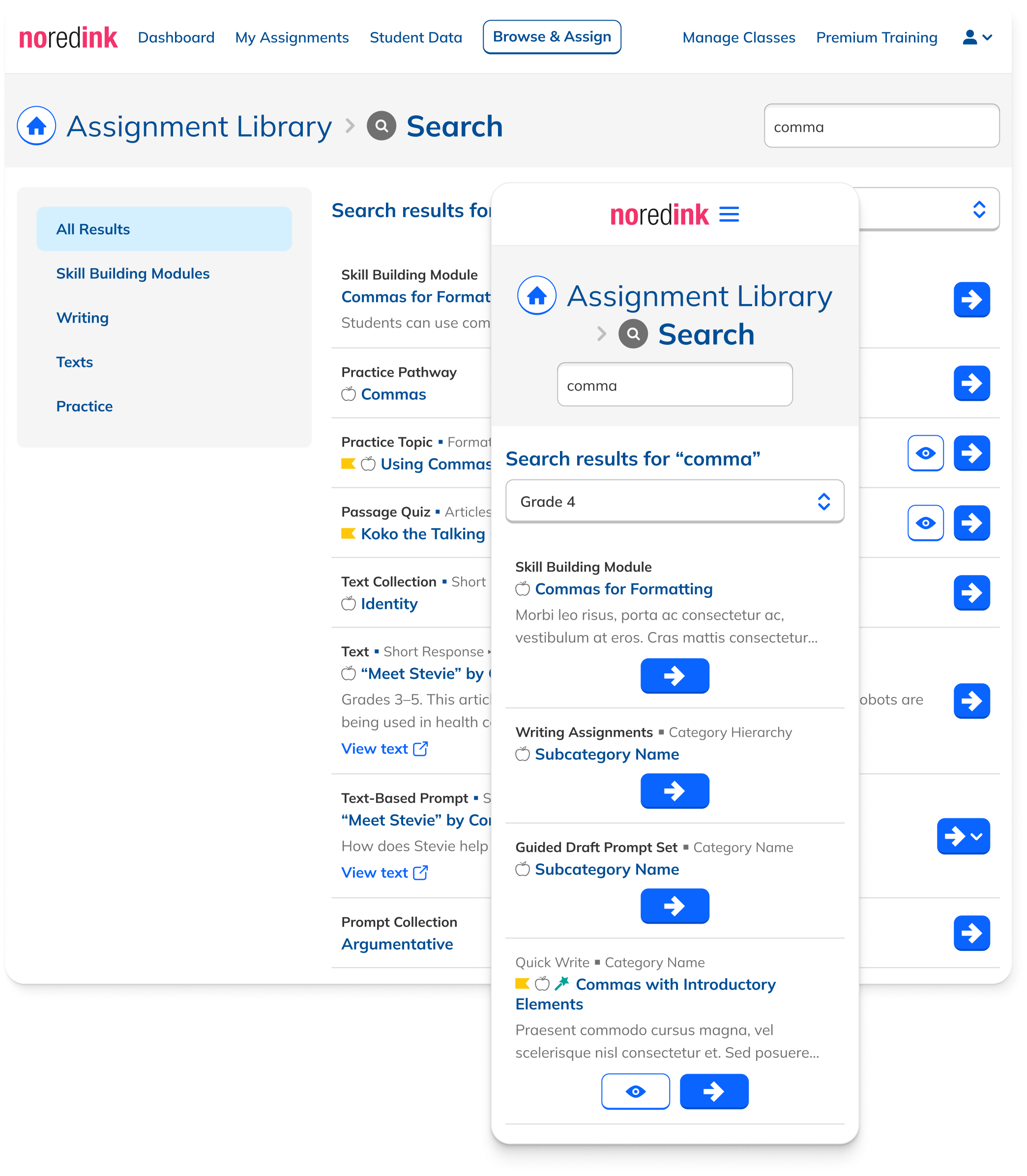

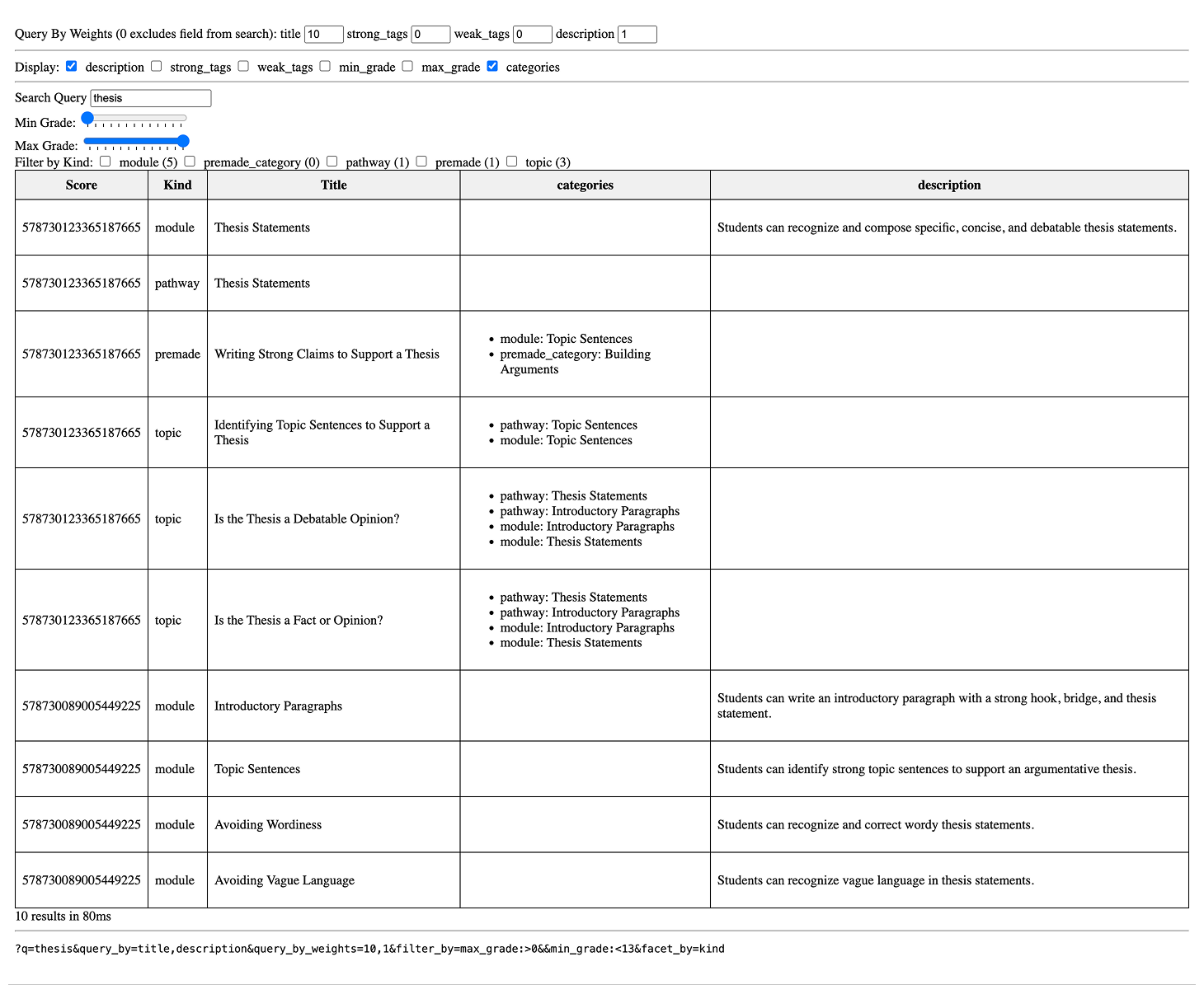

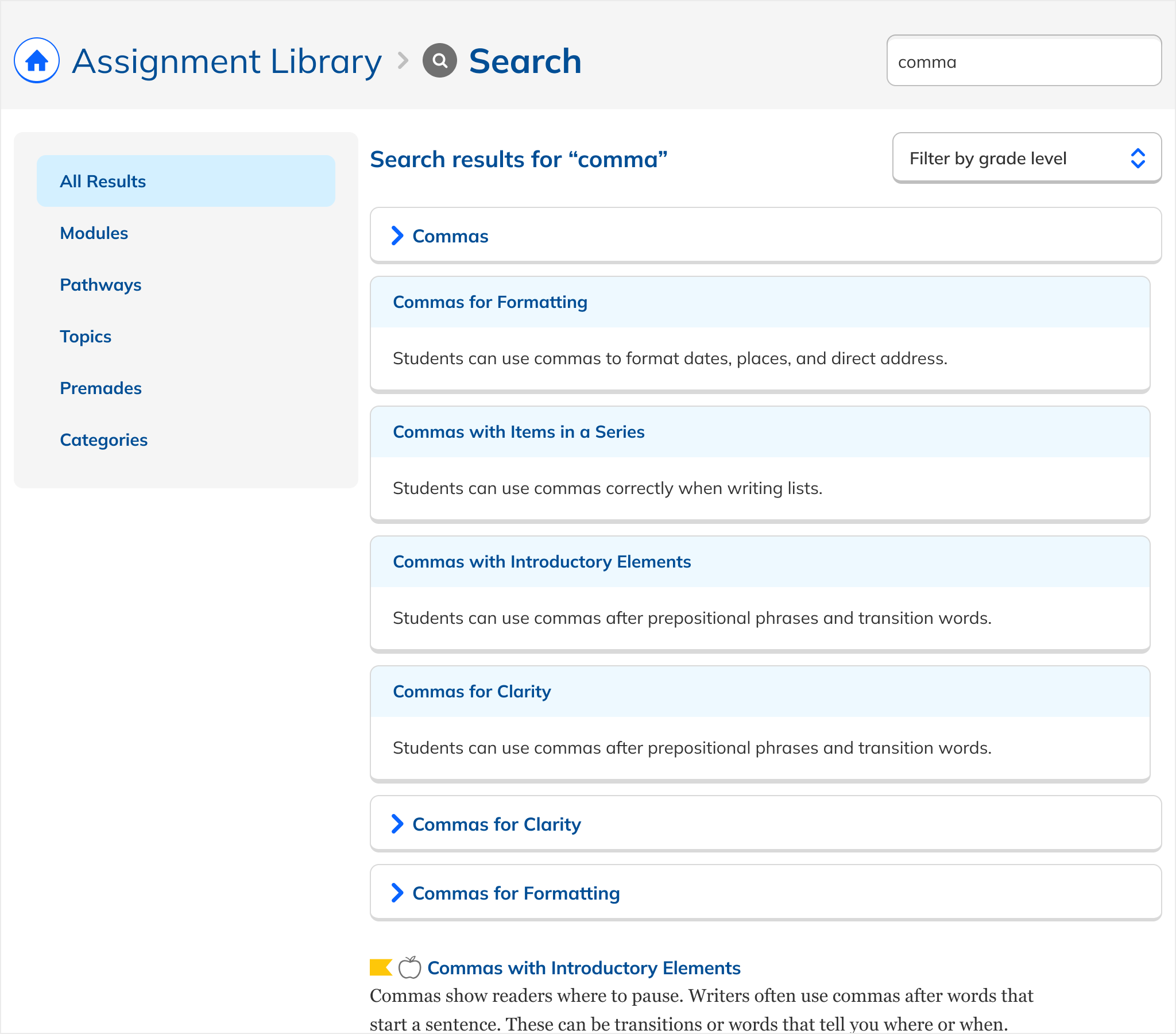

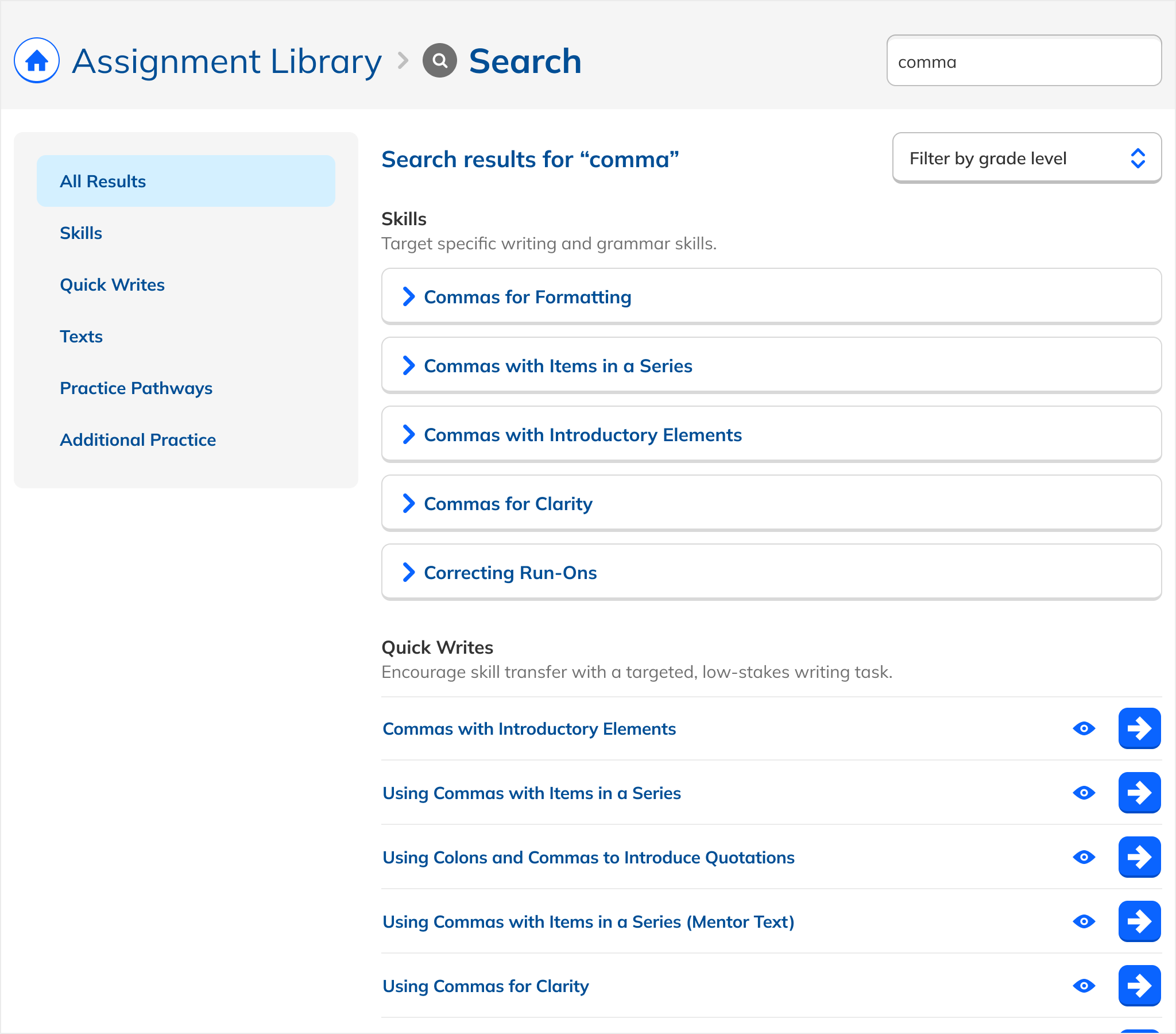

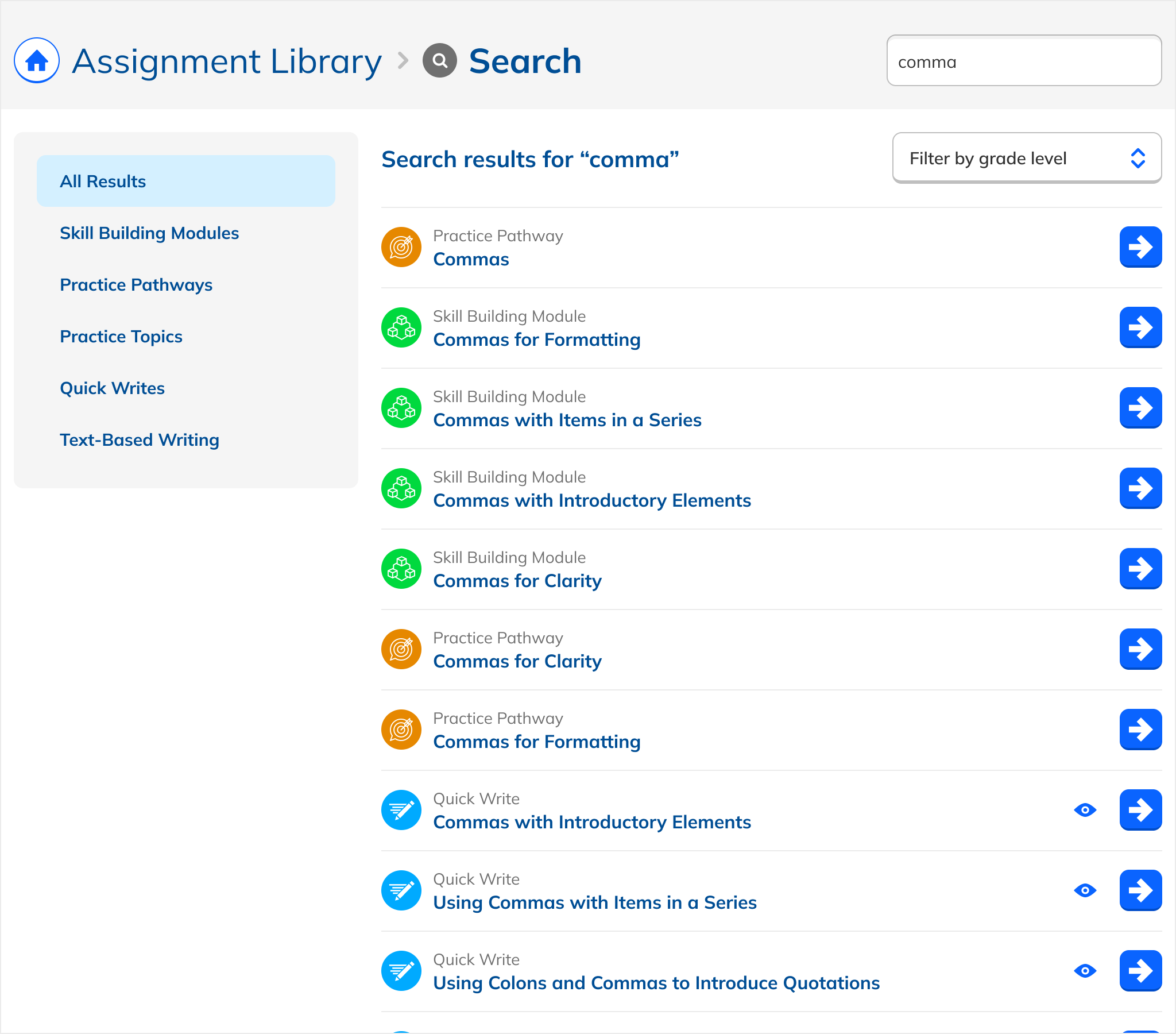

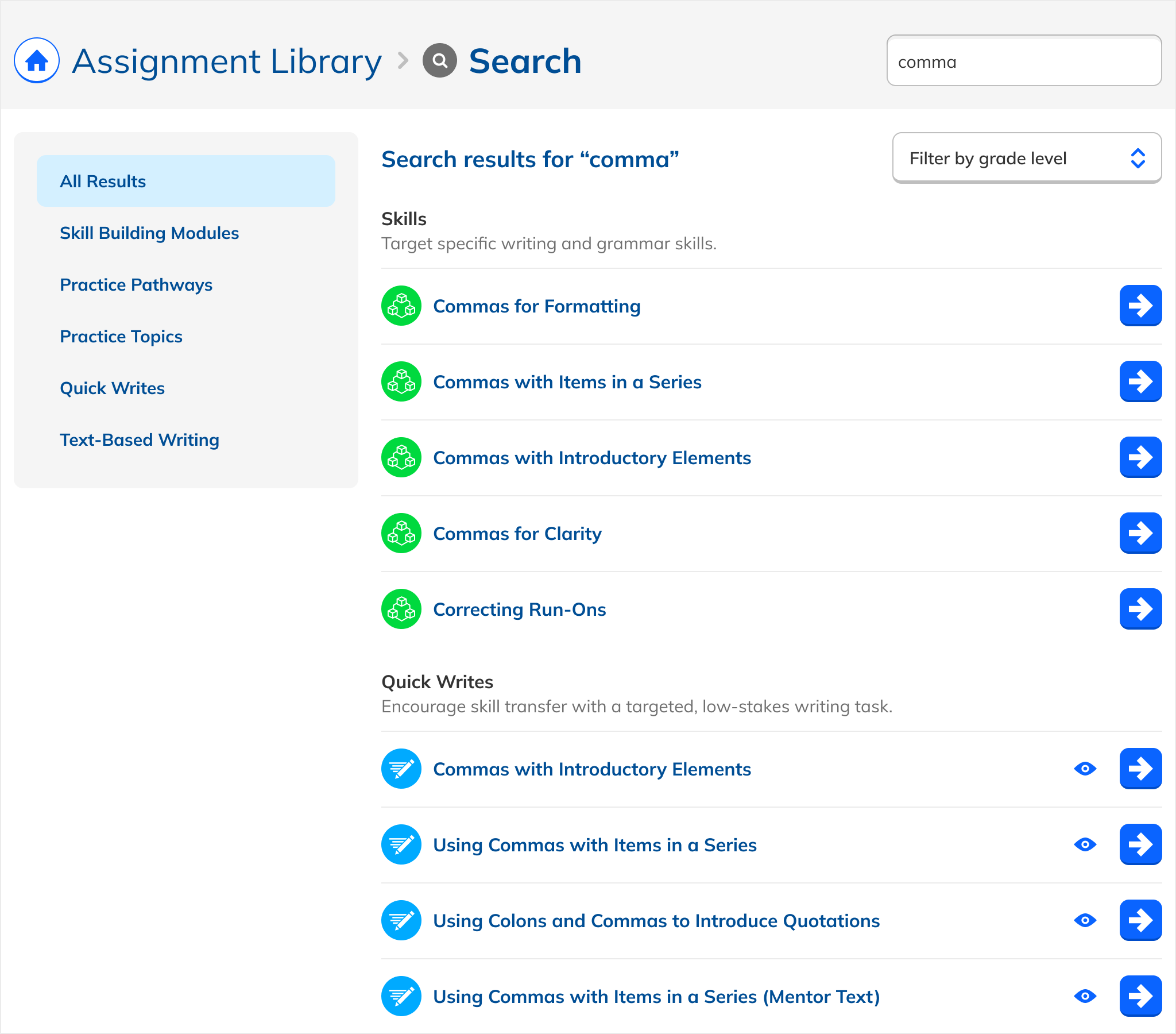

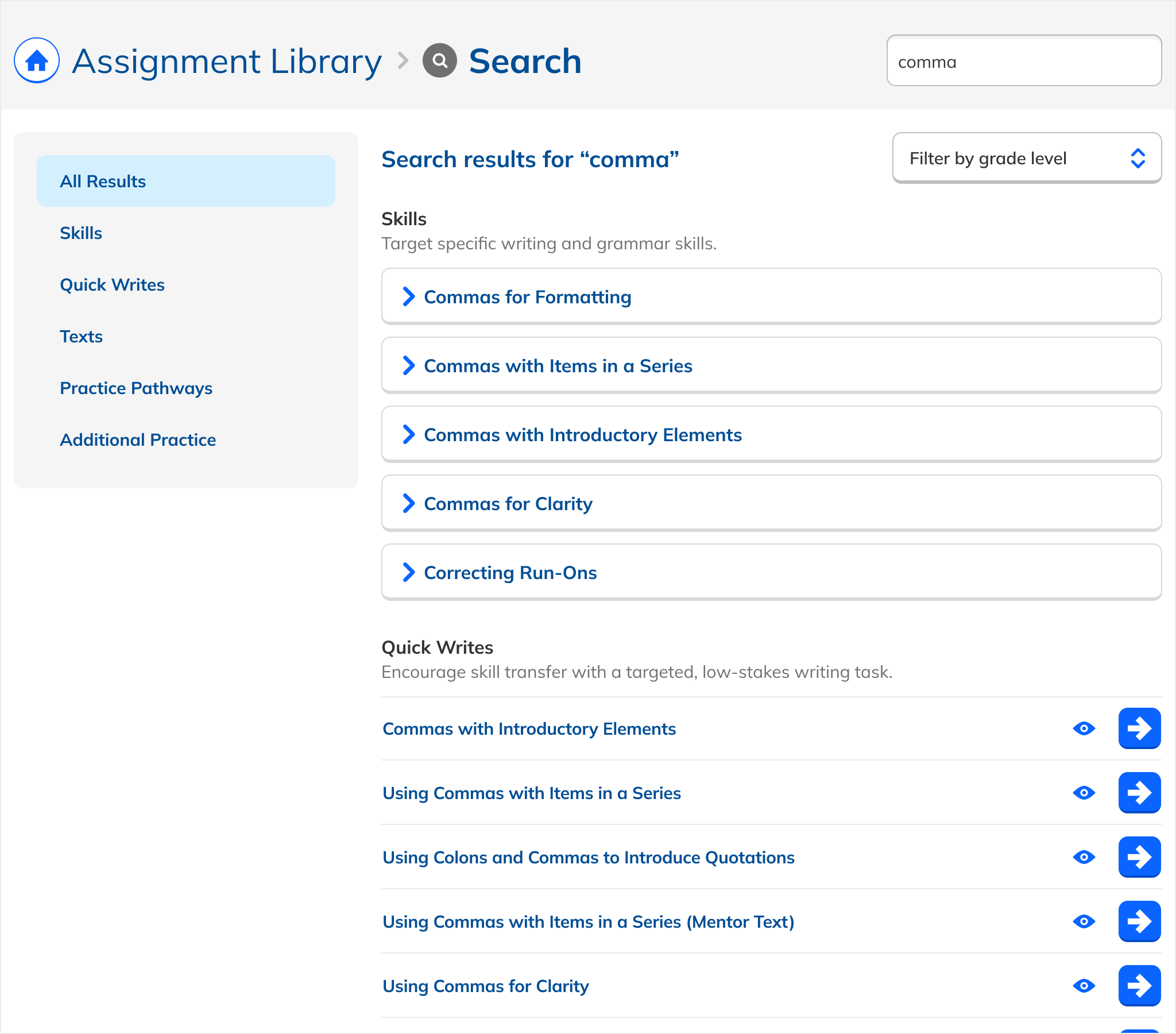

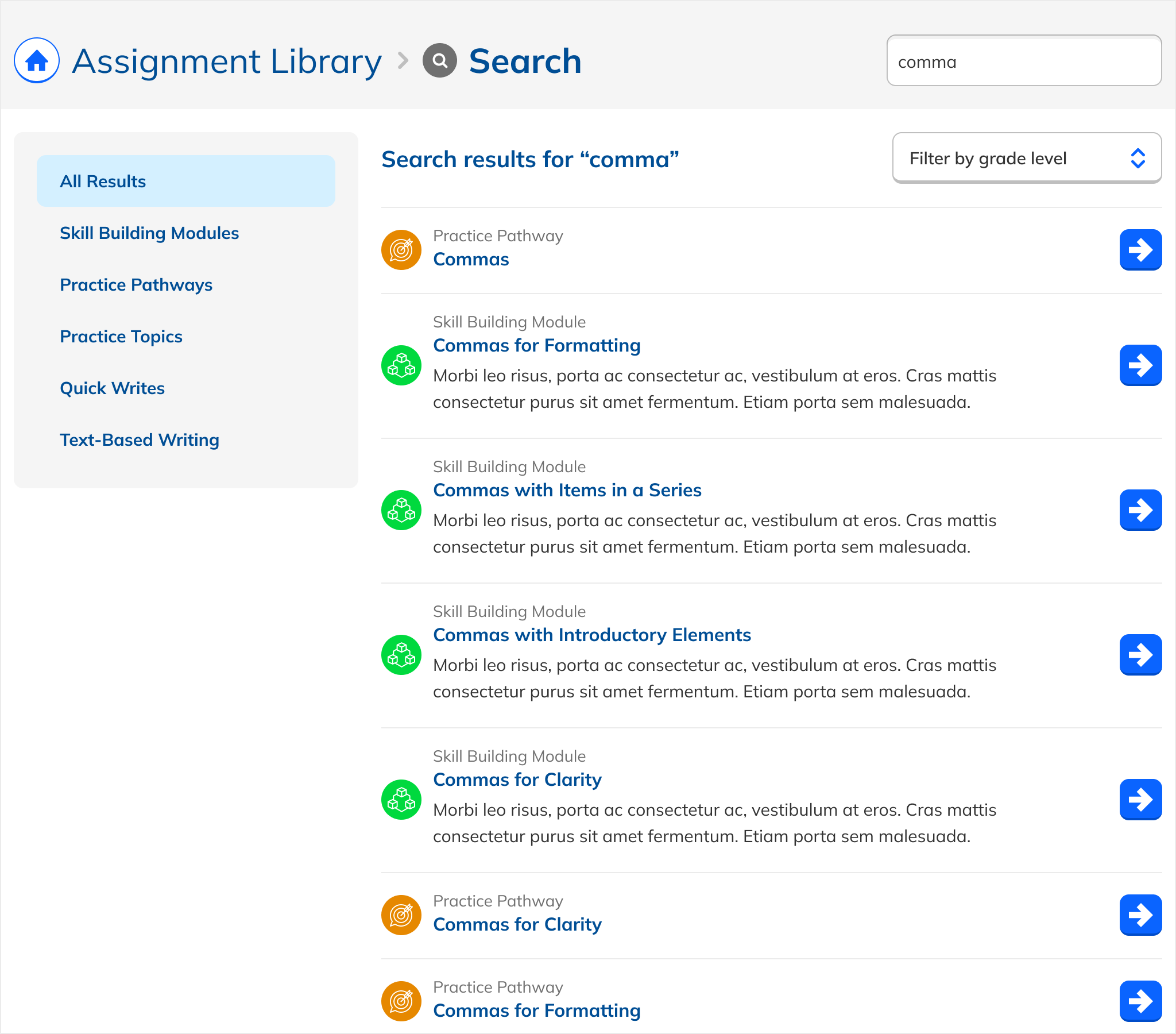

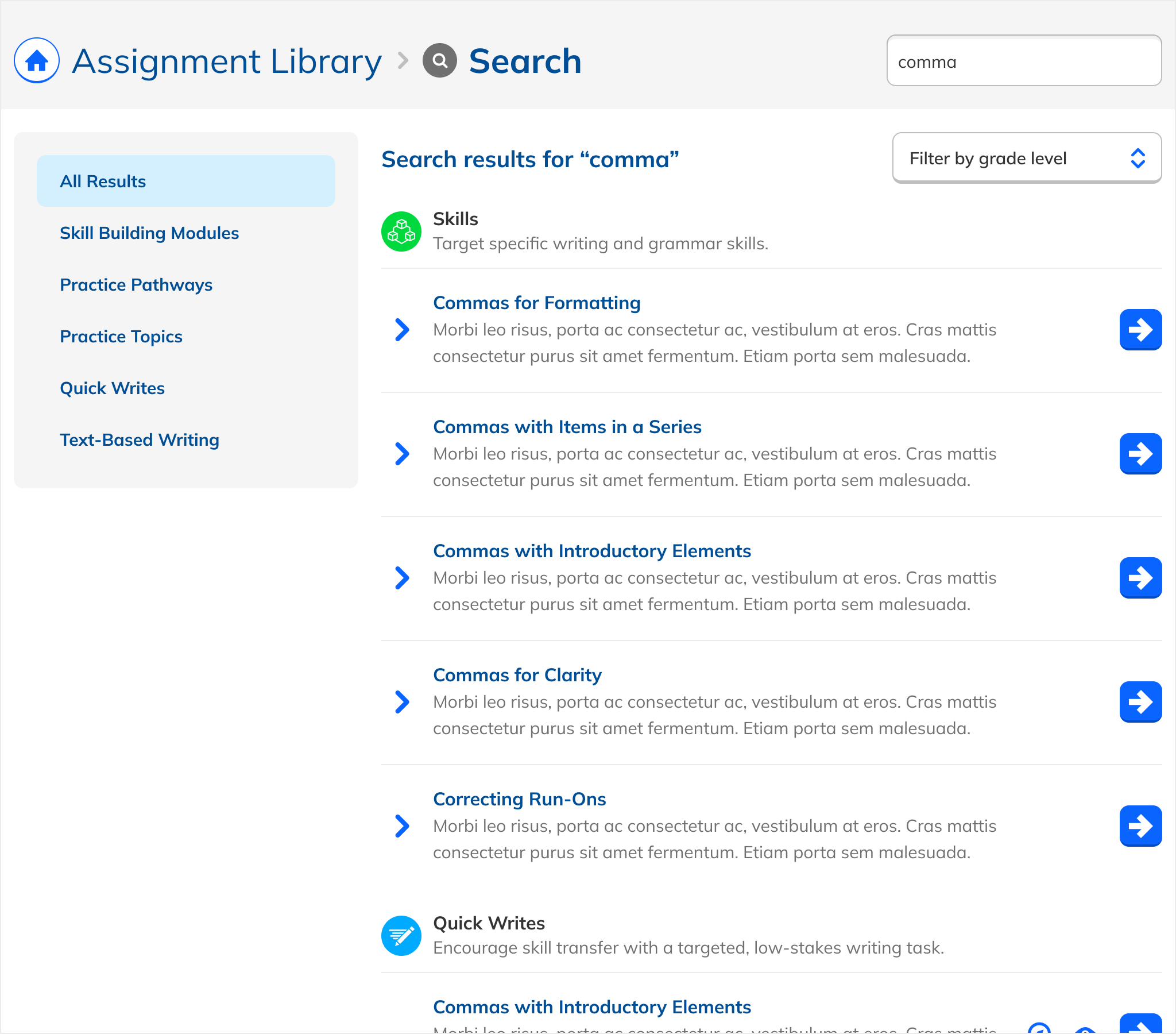

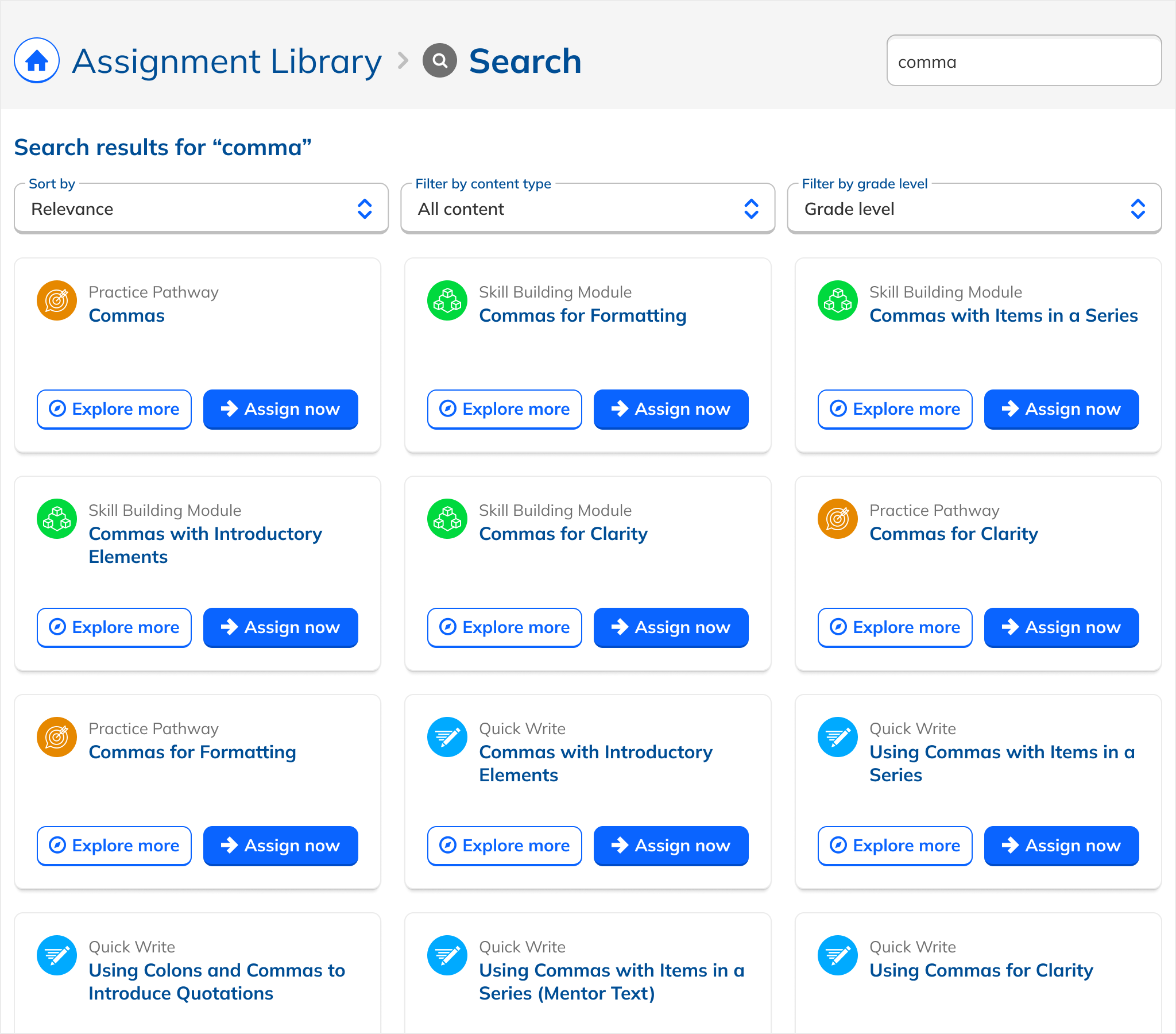

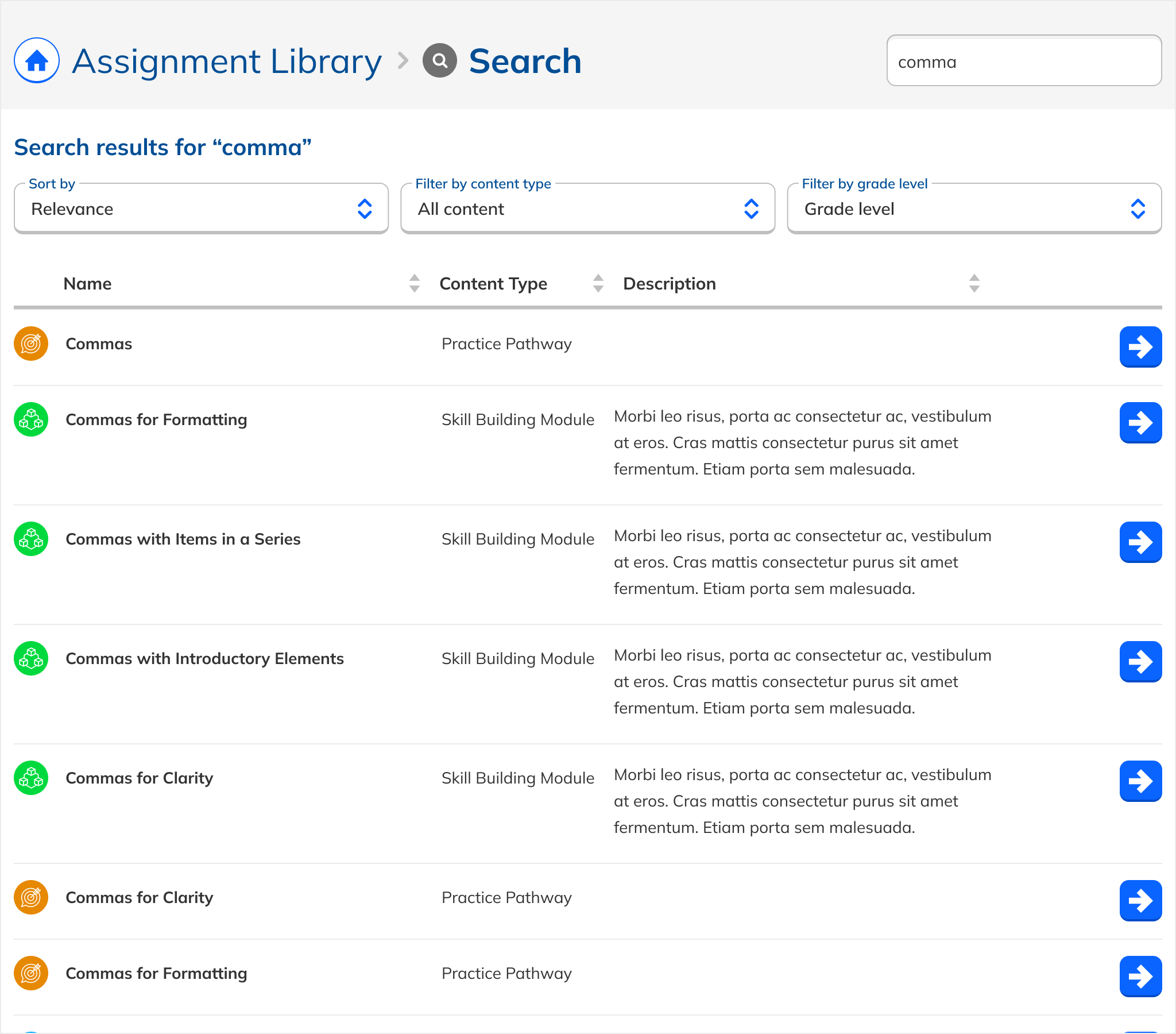

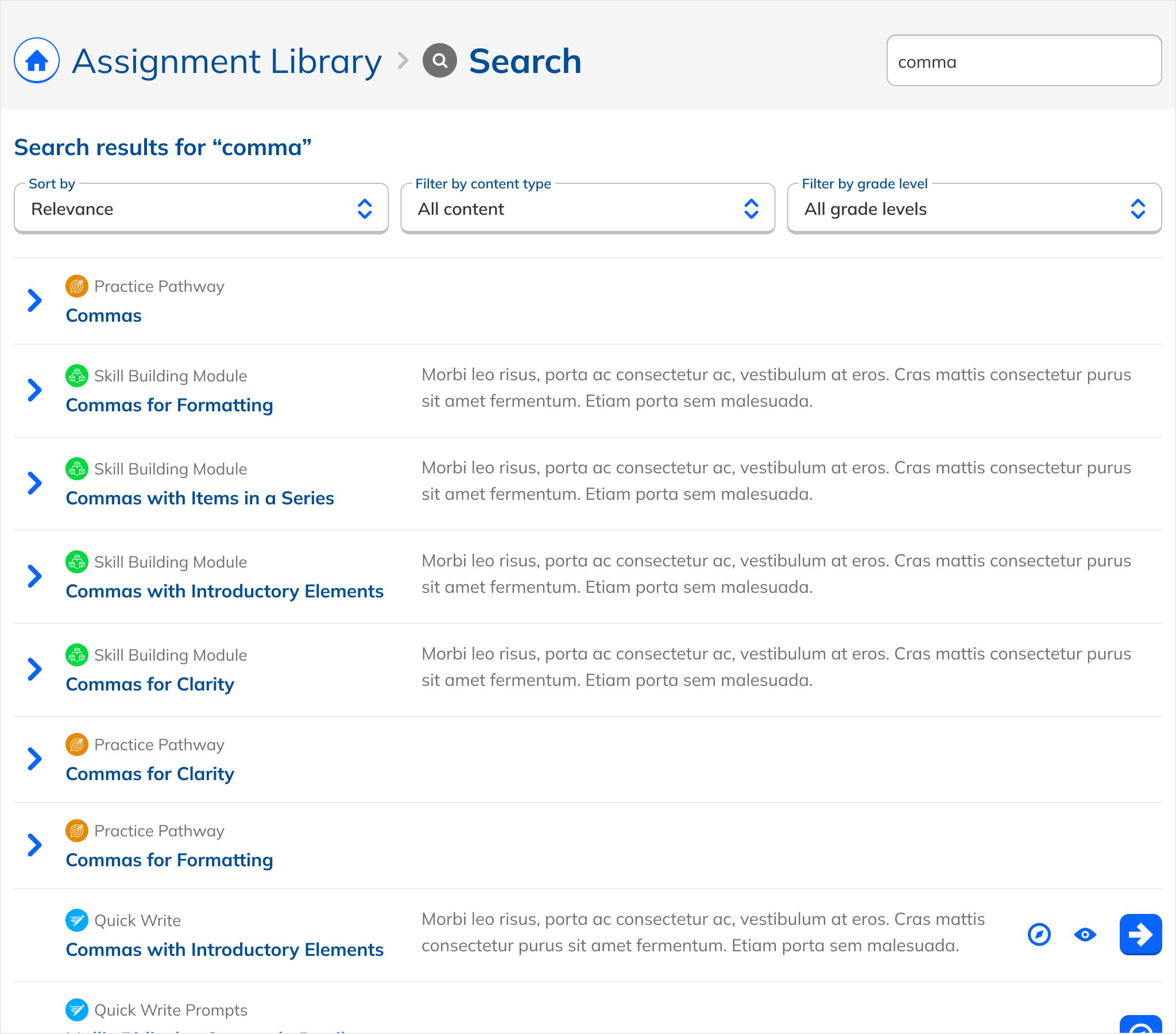

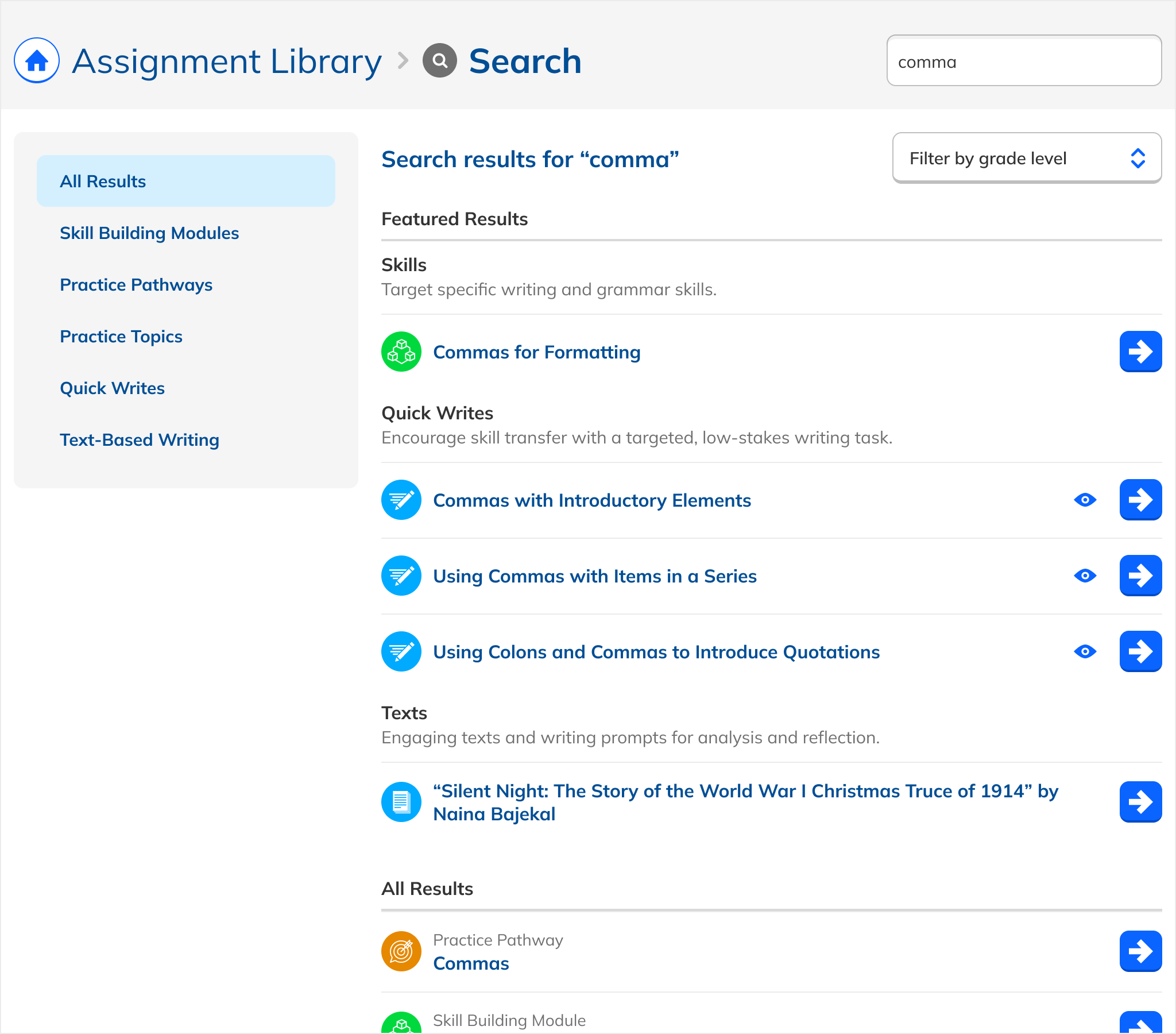

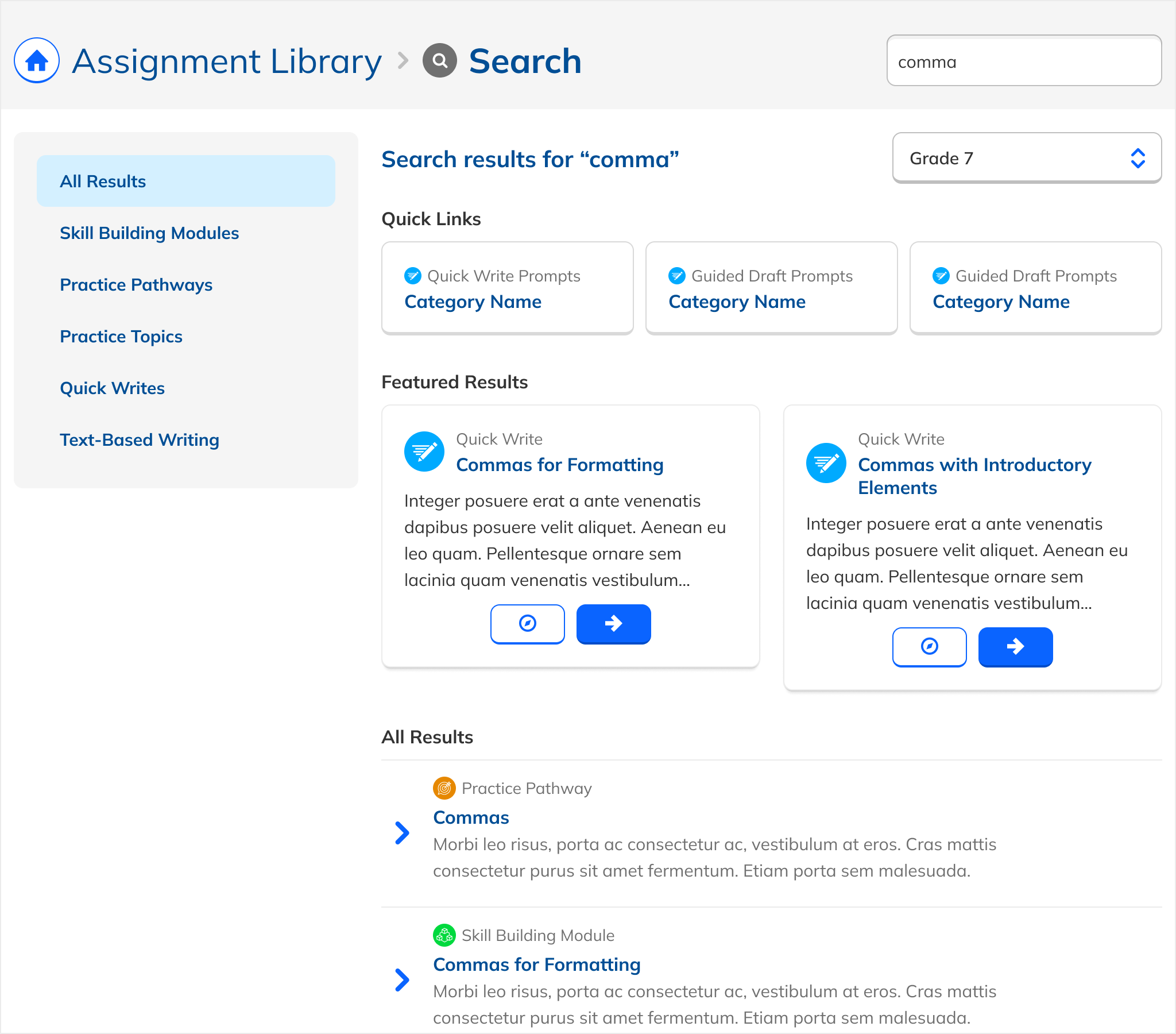

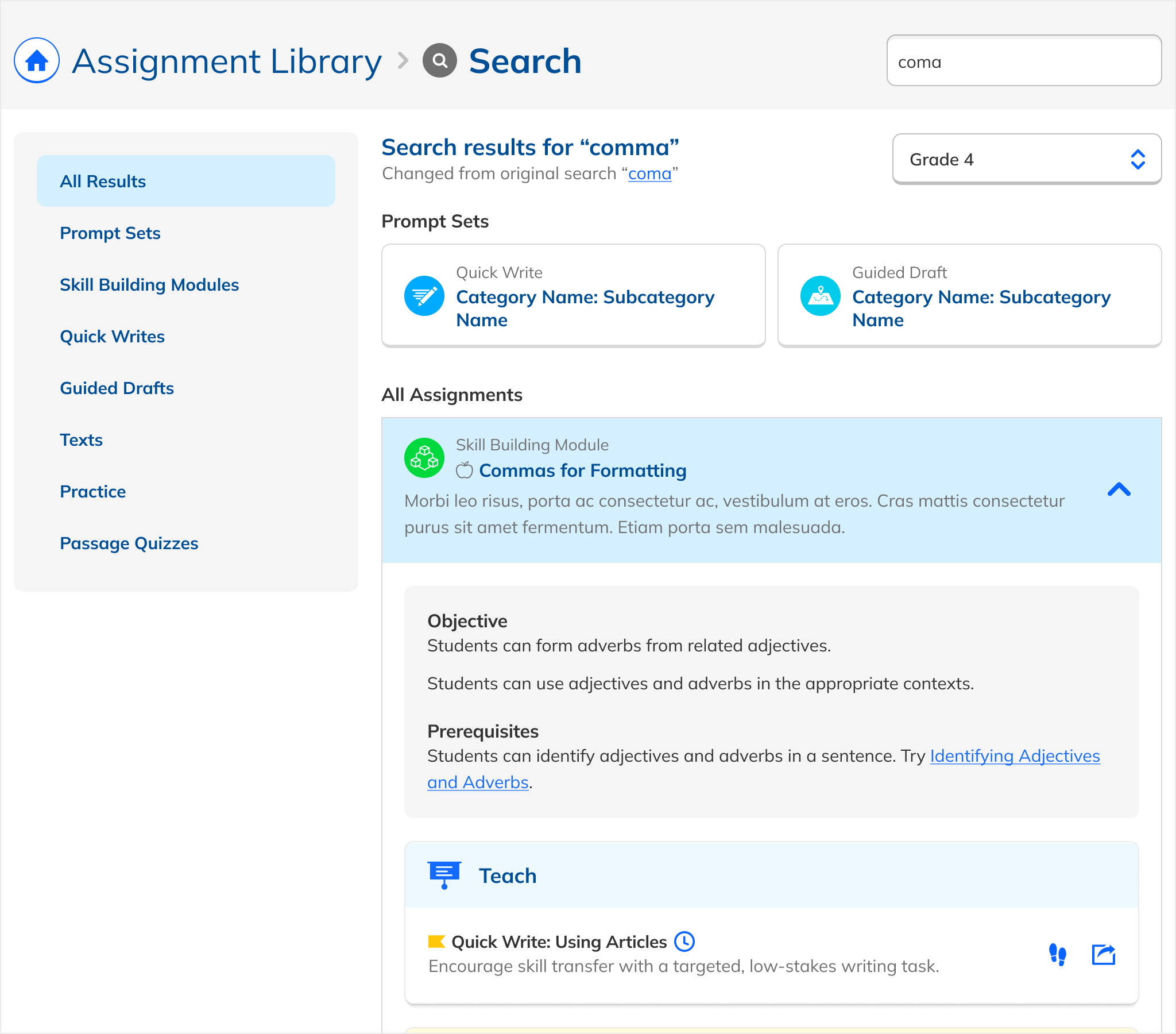

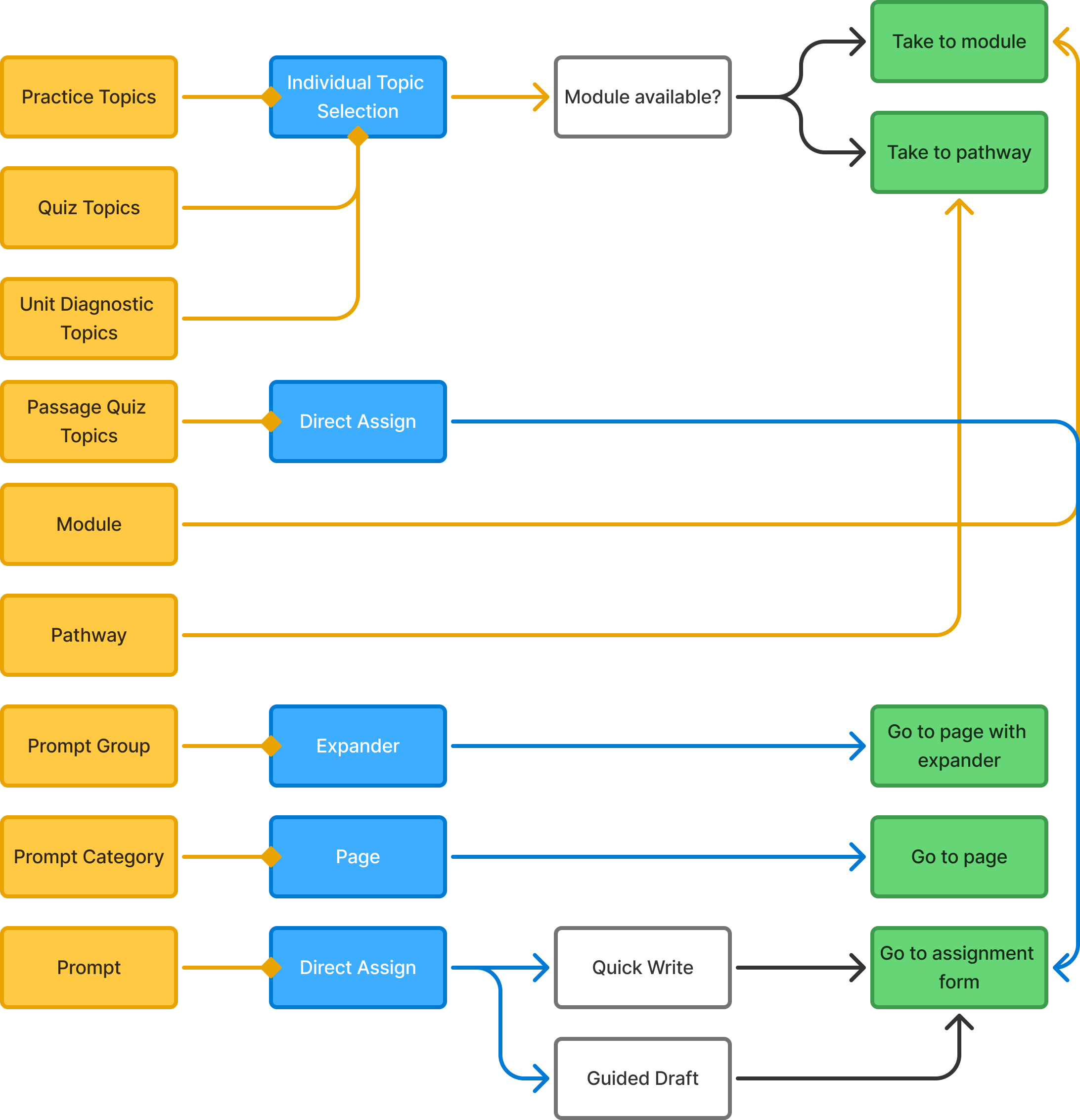

NoRedInk's Assignment Library is vast, containing thousands of pieces of content. This content is heterogeneous, coming in several different forms and organized in several different ways to meet teachers where their needs are. That organization is vital to making the Assignment Library a critical and useful part of the NoRedInk experience, but not all users have the time or inclination to browse through it all. That's where Search comes in. Search is both the universal fallback for all users and the first choice for some users on any platform.

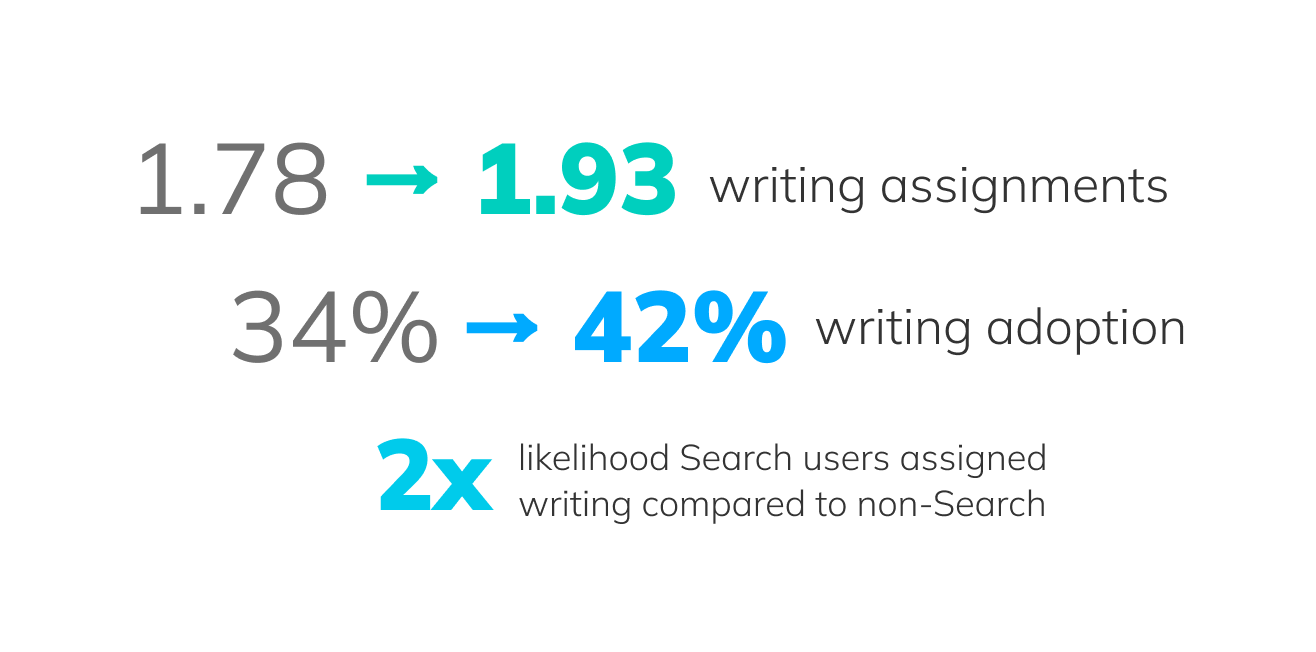

However, NoRedInk's search function left much to be desired. It was slow, buggy, and most crucially, did not return all of our content, reflecting badly on the platform and hobbling its utility. These facts alone were unfortunately not enough to get Search prioritized for an upgrade. However, a larger company goal to increase the assigning rates of assignments teaching writing and critical thinking skills (versus "mere" grammar skills) eventually came around and provided the opportunity we needed to not only strive to reach a business goal but improve the experience for our users.